Or, perhaps more accurately, we could argue that it is only the title of the plate that gives the “tavola” its centrality within a veritable cascade of images. And yet it would be just as possible to believe we are looking at stone blocks of varying proximities, against each of which rests a picture frame. The block is flanked to its left, at a recession, by another, similar, stone block.

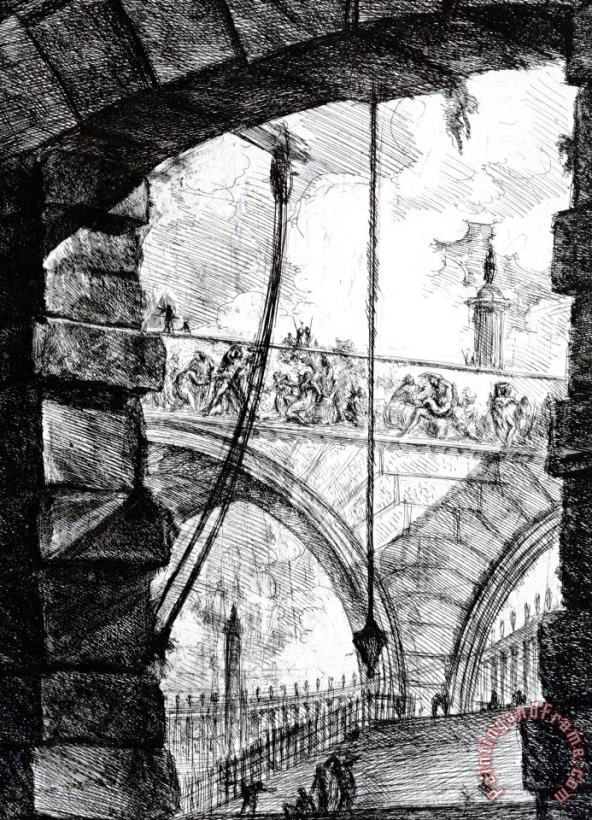

1749) from the grotteschi evokes a kind of trompe l’oeil, indicating the word for the engraving plate itself, la tavola, as well as what might be considered to be the monumental central image it presents - the tabula rasa facade of a stone block framed by an egg-and-dart border on which rest, or are hung, several cameos of figures in ancient drapery. The very title of La Tavola Monumentale (ca. 4 In the course of the development of his work, he displays a vertigo-inducing facility for moving between the page and the architectural space. In his preface to his four-volume work of 1756, Le Antichità Romane ( Roman Antiquities), Piranesi explains that he plans to re-create Roman space on paper: “When I saw the remains of the ancient buildings of Rome lying as they do in cultivated fields or gardens and wasting away under the ravages of time, or being destroyed by greedy owners who sell them as materials for modern building, I determined to preserve them forever by means of engraving”. His "speaking" ruins - glimpses and vistas alike, broken open and inside out, vanishing and revealing at once - inspire his life-long pursuit of the reality of the past, his methods shaped by his over-arching commitments to speculation and artistic freedom. 3 These early works by Piranesi already indicate the promise of what we might call a "paper architecture": an evolving practice that eventually will bring together exacting details of first-hand observation and the farthest reaches of the draughtsman's imagination. In a period of less than a decade, he went on to publish his fantastic architectural images of the Prima parte, worked out plans for two drawing series, the grotteschi (grottos or grotesques) and the carceri d’invenzione (imaginary prisons), and began the production of his first set of Vedute di Roma. When, out of funds, he returned to Venice, he frequented the studios of Tiepolo and the engraver Giuseppe Wagner and eventually, in 1747, returned to Rome as Wagner’s agent. With his move to Rome in 1740 as a draftsman in the retinue of the Venetian Ambassador Francesco Venier, Piranesi could be found working in the bottega of Giuseppe Vasi by 1742, continuing to develop his skills as a printmaker, and exploring the archaeological sites at Herculaneum in 1743. 2 His brother Angelo, a Carthusian monk, provided him with lessons in Greek and Latin and a knowledge of ancient history, studies that fired him with zeal for classical antecedents. Piranesi’s fascination with stone and vaults, particularly on a “magnificent” scale, evolved from his family’s long interest in the origins of architecture in general and Roman monuments in particular. 1īorn in 1720 in Mogliano Veneto, near Mestre, Piranesi was the son of a stone mason and throughout his life described himself as a “Venetian architect”. Their most well-known student, the eighteenth-century Venetian and Roman engraver-architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi, called them, in the dedication to his 1743 Prima parte di architetture, e prospettive, “queste parlanti ruine”: “these speaking ruins”. They call for an active, moving viewer - often a traveler with a consciousness distinct from that of a local inhabitant - who can restore their missing coordinates and names. In the present they are fused, almost always destructively, with their immediate natural environments. They lose their original purposes and have the singularity of artworks, yet they are severed irremediably from their contexts of production. They stand poised between the forms they were and the formlessness to which, in the absence of restoration, they are destined.

These often massive and almost always empty material structures are both over- and underdetermined. They do not follow or precede - they call for the supplement of further reading, further syntax. Anomalies in the landscape of the present, ruins are the architectural equivalent of the syntactical anacoluthon, or non sequitur.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)